Jean-Claude Trichet: Interview with El País

Autor: Bancherul.ro

Autor: Bancherul.ro

2011-05-16 13:08

Interview with El País

Interview with Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the ECB,

15 May 2011

Question: How would you describe the situation of the euro?

Answer: We are in an economic and monetary union. From my point of view, Monetary Union has worked well: we have delivered price stability – fully in line with our definition of “below, but close to 2% – during the first 12 years of the euro, the euro is a solid and credible currency, and inflation expectations are solidly anchored over a horizon of five or ten years. The Economic Union, for its part, has shown its weaknesses during this global crisis and it has to improve very significantly. All pillars of the Economic Union have to be reinforced: first, we need a strengthened Stability and Growth Pact to ensure a rigorous surveillance of fiscal policies; second, we need a close surveillance of the competitiveness indicators and of the imbalances in the euro area, something that we have been calling for all over these last years, since 2005; third, we need to accelerate the implementation of structural reforms, which is an objective for the economic union (the “27”) as a whole, as well as in the euro area (the “17”), in order to elevate the growth potential of European economies.

Q. What’s behind the dissatisfaction that seems to be affecting the euro?

A. I think there is criticism of the behaviour of some governments regarding their own economic and fiscal policies, and also on others, because they did not exert appropriately the surveillance on their peers. . But I don’t think the criticism concerns the single currency, which is a clear success. I have seen many surveys in different countries showing that citizens are supporting the euro. That is the case in Spain.

Q. Does rising debt indicate that the euro may be at risk?

A. As I said, the euro is a solid and credible currency. The economy of the euro area as a whole is in a better fiscal position than the US or Japan, with a likely deficit of 4.6% this year compared with around twice that figure in the US or Japan. Sovereign debt problems are global, not just a European problem. The paradox is that, while fiscal performance at the consolidated European level is relatively good, we have in the euro area some countries which are clearly in a difficult situation, and that require a major adjustment.

Q. Despite your rejection of a possible restructuring of Greek debt, markets are insisting that that is the only way out.

A. The ECB's position has been clear from the beginning. We have an adjustment plan set by the IMF and the Commission. What we are asking for is that the plan be implemented as strictly as possible, as it was negotiated, with rigorous efforts being made by Greece. The adjustment, engaged by this country is essential for its sustainable, medium term growth, job creation and the stability in the euro area. And there is no other way than the strict application of this adjustment plan.

Q. What can we expect from the summit in Brussels on Monday?

A. The Ecofin and the Eurogroup will have to examine a number of issues, including the programme for Portugal, which has been negotiated by the IMF and the Commission, in liaison with the ECB. The ECB attaches a great importance to the fact that this programme has been approved by various political sensitivities in Portugal.

Q. Has it been ruled out that a country could leave the euro?

A. I already said that I consider this an absurd hypothesis. But let me come back to the euro. If, in 1998, we had been told that for the 12 first years of the euro, we would have a single currency that keeps remarkably its value, with average inflation below 2%, a better result than in any Member State in the past 50 years, many people would probably have said that it was too good to be true. Today it’s a reality and these achievements are documented.

Q. Is the standing of the ECB at risk because of the rating cuts for the countries from which you have collateral?

A. We are applying our own rules on the matter and are paying close attention to risk management. It is also useful to bear in mind that we are talking about three economies that account for around 6% of the GDP. The other 94% of the GDP of the EU are in a very different position.

Q. The ECB has embarked on debt purchasing but is doing it intermittently.

A. I've always said we are transparent in the management of this issue. I have no other comment.

Q. But that is a function that is not supposed to be performed by the ECB, it is not part of the mandate. Should another institution take on that task?

A. All these non-standard measures have been decided by the Governing Council to better transmit our monetary policy decisions, in times of financial crisis. It is fully in line with our mandate. These measures, including the full allotment of liquidity at fixed rate, are transitory by nature, as I say regularly in the name of the Governing Council.

Q. Three years after the start of the crisis, where are we now?

A. Since the recovery started in the third quarter of 2009, Europe’s economy has experienced often upward revisions to previous projections of real growth. Quarter after quarter, the data has frequently exceeded expectations. This has been particularly evident in the first quarter of this year, with an increase of 0.8% more than projected, and several economies in the euro area with better results, even significantly better than expected. That includes Spain, which is growing a little bit better than anticipated. It is no time for complacency, we have to be very cautious and we do not declare victory, but I think that's encouraging. As for the role of the ECB, we are responsible for issuing the currency for 17 countries and 331 million citizens. That is a huge responsibility and it is normal that sometimes there are countries that go faster and others that go slower. What matters is that it’s not always the same ones who go rapidly or slowly because that would be unsustainable. There was a time when Greece and Ireland were growing very rapidly and then it was Germany that was lagging. So it's good that there are now countries, including Germany, which are growing again fast and quickly recovering the ground they lost, while others need to undertake indispensable major adjustments. Again, what counts is that in the euro area as a whole the recovery is confirmed. But let us not be complacent, we have hard work ahead of us.

Q. Oil prices have fallen by more than USD 10 since the ECB decided to raise rates. How do you see price stability at the moment, with raw material prices so volatile?

A. The decline in oil prices is good news: it reduces both the inflationary impact and the depressive effect of high oil prices on the economy. That said, there is a high degree of volatility. The present price level is high; 2.8% in the euro area. We cannot do anything immediately to reduce the price of oil and raw material. We have to ensure that price setters and social partners fully understand that we are there to deliver price stability in the medium term at less than 2%, close to 2%. It would be for them a big mistake to think that the present hump in the CPI inflation signals the level of inflation in the medium term. Because we are there to take decisions that will prevent this. That’s why there is an independent central bank – to ensure price stability over the medium term.

Q. Are you seeing excessive wage increases?

A. Let me say something to the people of Spain: we are providing price stability in line with our definition, an average of 1.97% in the first 12 years, we are credible for the future five to ten years, and that has to be accounted for in all decision-making within the euro area. If prices and costs in a particular economy are permanently above that level, with spiralling of nominal inflation and nominal wages, in particular there will be unavoidable losses in competitiveness and less growth and less job creation.

Q. Does that apply to Spain in particular?

A. To all countries, without exception, and of course to Spain also. This is a very important message.

Q. So those involved in wage negotiations should forget about national price data.

A. All price-setters, in particular the social partners, must be conscious that there is a benchmark for the euro area inflation as a whole, which is less than 2%, close to 2%. If the unit labour costs in particular are not in line with the evolution of the euro area as a whole, a loss of competitiveness of the economy will be unavoidable, with its consequences in terms of growth and jobs creation. Again, the worst that could happen in terms of growth, is a cost/price signalling over and above the average of the euro area.

Q. That is the conclusion that many people are drawing about the situation in Spain, do you share it?

A. Some of these phenomena happened in the past undoubtedly. It seems to me now that everybody understands that competitiveness of the productive sector is essential for the economy.

Q. It is doubtful that the citizens of southern Europe understand the rise in rates resulting from the threat of inflation.

A. I think they understand. Because if we were to lose credibility in price stability, then inflation expectations would not be anchored and all medium- and long-term market interest rates in Europe, would rise, driven by those higher inflation expectations. Then we would all, I insist, all without exceptions, be suffering the consequences of a less favourable financial environment and its impact on growth and job creation.

Q. This is very reminiscent of the situation in July 2008. Are you still defending that rise in interest rates?

A. Of course it was an appropriate decision. The collapse of Lehman Brothers came later and we took the right measures to cope with the dramatic crisis. We decided to raise rates to counter an unwelcome increase in inflation expectations. By taking that step we confirmed that we are extremely determined to anchor inflation expectations. It helped us considerably during the crisis in preserving us both from the materialisation of the risk of inflation as well as the materialisation of the risk of deflation – which was a very important element to surmount the crisis.

Q. Jürgen Stark has said that the debt crisis is our own Lehman Brothers.

A. We are experiencing at the global level a second episode of the crisis. After the private-sector crisis we are now seeing tensions in the public sector and amongst sovereign risks. This is a global phenomenon, observed in advanced economies. It’s crucial to deal with these tensions correctly, especially in Europe.

Q. Let's turn to Spain. Don’t the markets understand the reforms that have been made?

A. From our point of view, there are three key issues: fiscal policy, the financial sector and structural reforms. Spain is moving in these three areas, it has made decisions; it has set goals and has done a lot, and has still work ahead of it. I'd say that this is appreciated by external observers, who believe that the country is going in the right direction. But this is no time for complacency. On the fiscal side, the government has been convincing. That being said, measures have to be followed up and the deficit target of 3% in 2013 is essential for credibility. Regarding the financial sector, there is a huge difference in perception compared with a few months ago, but work has not been finished there yet. As for structural reforms, they are absolutely essential because it is through them that growth potential increases. There are reforms that need to be tackled, especially labour market reform, which is being discussed by the social partners. All this is true for Spain, but also for Europe, which has to push forward bolder structural reforms.

Q. Isn’t fiscal orthodoxy, the surge of austerity, condemning Europe to slow growth for a long time?

A. On the contrary, fiscal soundness is essential for confidence, and confidence is the most important ingredient for sustainable growth. Financial soundness and structural reforms are also of essence. But speaking for the past, let me give you two or three figures. In the past 12 years, GDP per capita has grown in Europe at the same pace as in the US, around 1%. In the labour market, despite the years of crisis, the euro area has created around 14 million jobs since the birth of the euro: about 6 million more than in the US. This is again no time for complacency. And nobody can say that we are satisfied when unemployment is still so high.

Q. Is Spain the red line in the EU?

A. Spain in the past has shown a remarkable capacity for innovation, for creativity, growth and job creation. It is a very dynamic country. That makes me optimistic, provided Spain continues to implement very actively and convincingly its programme in three areas already mentioned: fiscal soundness, banks’ reshaping, and structural reforms.

Q. And the savings banks are the red line in Spain?

A. In this sense, Spain has three main challenges. As regards the savings banks challenge, a lot of hard work has already been done and should continue to be very actively performed.

Q. Especially after the leaks in Germany, do you think all the European partners, especially the political leaders, are aware of the danger of the current fiscal situation?

A. I appeal to all governments to show a high sense of responsibility, both individually and collectively, and to keep a strong sense of direction.

Q. At first you didn’t seem very happy about the IMF involvement in the bailouts. Some were even calling for a European Monetary Fund. Why did you change your point of view?

A. The worst thing would have been benign neglect by the Europeans, which was a big danger at the beginning. Having overcome this temptation, the rescue brought together the conditionality and the financial support from the IMF and the European partners, which was necessary.

Q. On the subject of eurobonds, Europe has no treasury, unlike the United States. Do you think that a step could be taken in that direction?

A. At the present stage of European integration, with the current institutional framework, we consider that a major improvement in governance, particularly in fiscal policy, is absolutely decisive. At this stage we are not in favour of euro bonds.

Q. What is your opinion of Zapatero?

A. It is not for the President of the ECB to judge or give good marks or bad marks to the prime ministers! We are fiercely independent from the executive branches and we are issuing the currency for all the people, all the 17 nations, and political sensitivities.

Q. What about Draghi?

A. The appointment of the President of the ECB is the responsibility of the Heads of State and Government, after having had the advice of the Parliament and the Governing Council of the ECB.

Q. Does he have the right profile?

A. We have a great Governing Council, with very wise and experienced colleagues. And I have to say that Miguel [Fernández Ordóñez], Mario [Draghi] and all others have the right team spirit. And it is this very good team spirit which counts.

Q. What will you do after 31 October?

A. We'll see. I have a very hard job ahead of me. There’s no time for complacency in many ways. I still have five and a half month! I will be completely absorbed by my work until the end of October.

Q. In these eight years, what has been the worst moment? May 2010?

A. We have had major challenges from the start. Immediately after my arrival the largest countries in the euro area, Germany, France and Italy, were asking for an easing and even a dismantling of the Stability and Growth Pact. We had to fight that. And there were other big challenges afterwards; the crisis has certainly been one. This is the greatest crisis since the Second World War. It could have been even worse – the worst crisis since First World War – if we had not made the decisions we made. They were times that required a great deal of effort. It has been very rewarding to see the team spirit of the Governing Council and of the staff of the ECB and of the other central banks of the Eurosystem. There have been some intensely challenging moments, during which my greatest satisfaction has been to see a formidable dedication to the euro and to Europe, in serving our 331 million fellow citizens..

Q. What is your legacy?

A. It’s not up to me to talk about that.

European Central Bank

Directorate Communications

Press and Information Division

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Adauga un comentariu folosind contul de Facebook

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE. Iata textul publicat de BCE: DECLARAȚIE DE POLITICĂ MONETARĂ detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%. In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara. De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL). Comunicatul BCE Consiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor detalii

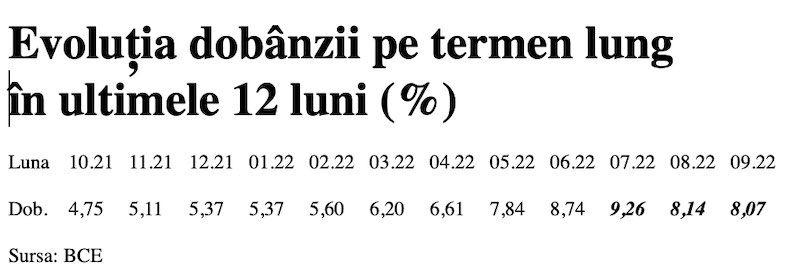

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen de 10 ani (10Y), a continuat astfel tendința detalii

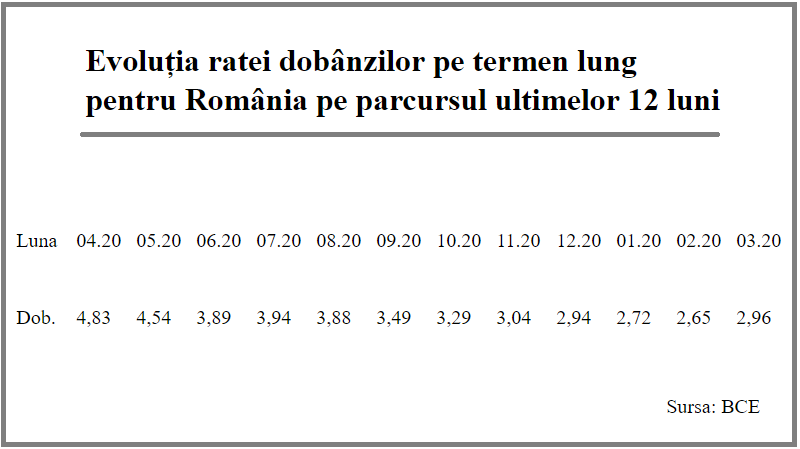

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobânzii pe termen lung pentru România a crescut la 2,96% în luna martie 2021, de la 2,65% în luna precedentă, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator critic pentru plățile la datoria externă scăzuse anterior timp de șapte luni detalii

- BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

- Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

- Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

- BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

- BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

- BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

- ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

- ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

- Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

- Deciziile de politica monetara ale BCE

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 18 miliarde euro după primele opt luni

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 9 miliarde euro pe primele cinci luni

- Deficitul contului curent, 6,6 miliarde euro după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul contului curent pe T1, aproape 4 miliarde euro

- Deficitul contului curent după primele două luni, mai mare cu 25%

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

- Parlamentul dezbate marti legile de plafonare a dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor cesionate de banci firmelor de recuperare (actualizat)

Anunturi banci

- Cate reclamatii primeste Intesa Sanpaolo Bank si cum le gestioneaza

- Platile instant, posibile la 13 banci

- Aplicatia CEC app va functiona doar pe telefoane cu Android minim 8 sau iOS minim 12

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

Analize economice

- România, pe locul 16 din 27 de state membre ca pondere a datoriei publice în PIB

- România, tot prima în UE la inflația anuală, dar decalajul s-a redus

- Exporturile lunare în august, la cel mai redus nivel din ultimul an

- Inflația anuală a scăzut la 4,62%

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, +7,3% cumulat pe primele 8 luni

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, 51,4% din PIB la mijlocul anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,6% din PIB după prima jumătate a anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,4% din PIB după primele cinci luni ale anului

- Deficit bugetar îngrijorător după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul bugetar, -2,06% din PIB pe primul trimestru al anului

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- ANPC pierde un proces cu Intesa si ARB privind modul de calcul al ratelor la credite

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

Stiri economice

- Datoria publică, 52,7% din PIB la finele lunii august 2024

- -5,44% din PIB, deficit bugetar înaintea ultimului trimestru din 2024

- Prețurile industriale - scădere în august dar indicele anual a continuat să crească

- România, pe locul 4 în UE la scăderea prețurilor agricole

- Industria prelucrătoare, evoluție neconvingătoare pe luna iulie 2024

Statistici

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului muncii în T2 2024

- Cheltuielile cu pensiile - România, pe locul 19 în UE ca pondere în PIB

- Dobanda din Cehia a crescut cu 7 puncte intr-un singur an

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

- O firma care a facut un schimb valutar gresit s-a inteles cu banca, prin intermediul CSALB

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Producția industrială, în scădere semnificativă

- Pensia reală, în creștere cu 8,7% pe luna august 2024

- Avansul PIB pe T1 2024, majorat la +0,5%

- Industria prelucrătoare a trecut pe plus în aprilie 2024

- Deficitul comercial, în creștere de la o lună la alta

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate

Ultimele Comentarii

-

Bancnote vechi

Numar de ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Am 3 bancnote vechi:1-1000000lei;1-5000lei;1-100000;mai multe bancnote cu eclipsa de ... detalii

-

Schimbare numar telefon Raiffeisen

Puteti schimba numarul de telefon la Raiffeisen din aplicatia Smart Mobile/Raiffeisen Online, ... detalii

-

Vreau sa schimb nr de telefon

Cum pot schimba nr.de telefon ... detalii

-

Eroare aplicație

Am avut ora și data din setările telefonului date pe manual și nu se deschidea BT Pay, în ... detalii